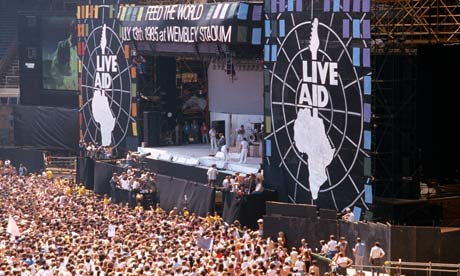

Live Aid Day was twenty-five years ago today; half a lifetime ago for me, give or take a few days. I meant to type a few words in its memory five years ago, but didn’t get round to it, so I’ll do that now. It was surely one of the seminal moments of post-war British popular culture.

I was very keen to record as much of the BBC’s coverage of the event as possible, so I bought two four-hour VHS tapes. Some time that morning I had the idea of connecting the stereo audio inputs of the family VHS recorder to our HiFi tuner, so I could record BBC Radio One’s stereo ‘simultaneous transmission’ in place of the BBC One (mono) TV audio. I drove round to a little electronic shop in Hartlepool’s unfashionable Murray Street shopping district to buy the necessary plugs and cabling, and I had soldered them together about twenty minutes before Status Quo kicked off proceedings at Wembley Stadium at midday. This worked beautifully, as it turned out. Stereo VCRs were exceedingly rare in those days; indeed they were almost pointless, and I suppose I must be one of very few people to have original video recordings of Live Aid with stereo audio.

My girlfriend at that time, Sara, had come round to share the occasion with me, and Live Aid Day is one of the happiest memories of that relationship. For some reason I can’t recall my parents had gone out for the day until quite late, and we kept ourselves entertained during the less interesting performances by having sex on the carpet or the sofa, about five times in total. She was seventeen years old; I was a dirty old man even then. To this day I feel slightly sore whenever I hear Dylan’s Blowing In The Wind.

And speaking of old men, it’s strange to think that Quo’s Francis Rossi and Rick Parfitt, even in 1985 considered middle-aged relics of a bygone musical age, were still in their mid-thirties. In the stagnant popular culture of the 21st century, music careers last much longer before they reach their sell-by date.

Interestingly it’s mostly the established artists from the ’70s who participated that are best remembered. The surviving members of the Who reformed for the day, although the transmission of their set was truncated by a power cut. Phil Collins performed on both stages, at Wembley and at Philadelphia. He took a helicopter from Wembley to Heathrow Airport and was in Philadelphia less than four hours later, something that’s not possible now. Later in the evening he played drums for a reformed incarnation of Led Zeppelin, in a performance rendered shambolic by Jimmy Page’s incoherent guitar playing. Eric Clapton’s set in the US sparked off something of a renaissance of his career.

And by any reasonable assessment, Queen were the day’s winners. Theirs was the performance that was destined to represent the spirit of the day for prosperity. Freddie Mercury projected his considerable presence into every corner of Wembley Stadium, into every corner of every living room with a TV tuned in to the show.

It was the first of a long tradition of high profile, international charity events that continues to this day, but none since has caught the popular imagination the way that Live Aid did. Politically, it had provided a new way to crystallise the public conscience into action, even if it worked partly by the power of self-congratulation. Musically and culturally though, I think it was a sort of high water mark. The colourful, flamboyant, naive charm of the ’80s seemed to ebb away slowly from that moment, as the likes of Duran Duran, Nik Kershaw, Culture Club and Spandau Ballet gradually gave way to soulless artists in double-breasted suits, singing records manufactured by Stock, Aitken and Waterman.

I’m not saying that the battle is won

But on Saturday night all those kids in the sun

Wrested technology’s sword from the hand of the war lord

Oh, oh, oh, the tide is turning

– Roger Waters, The Tide Is Turning (After Live Aid)