Years ago I became excited by the prospect of new formats for digital music reproduction, to replace the Compact Disc Digital Audio format (CDDA) format conceived in the 1980s. A number of competing formats emerged, all intended, ostensibly at least, to provide a more natural and rewarding listening experience by virtue of representing music in “higher definition” – SACD, DVD audio, more recently Blu-Ray audio.

I’ve had an interest in the techniques used by digital audio since I studied encoding methods as part of a Computer Science degree course, and as a technologist who loves music, I was intrigued enough to research the technology and principles that underpin these new formats.

I discovered that they were completely pointless.

Here’s how digital audio works, in simple terms. Any sound is experienced as variations in pressure against the ear drum – these arriving there by means of a sound wave. Audio recording is the process of capturing a representation of this sound wave, or ‘waveform’ by some means. Before the advent of digital recording, this was often done by representing the waveform by an electrical signal encoded as magnetism at continuously varying degrees of strength along the iron oxide emulsion bonded to a flexible film tape.

Digital audio works by sampling the waveform at regular intervals. These samples are stored as numbers representing the amplitude of the wave at the point it was sampled.

There are two essential dimensions in a digital recording, then. The first of these is the sampling rate, or frequency at which the original waveform is sampled. The second is the bit depth, or the number of binary digits allocated to store each sample – which represents the accuracy of the representation at that point in time. The CD audio format uses samples taken at the rate of 44,100 per second (44.1 khz), at a bit depth of 16 – so one second of CD audio is represented by 44,100 16-bit numbers. For this reason the CD format is sometimes referred to as 44.1/16.

Let’s consider the sampling rate first.

If you’re at all familiar with the principle of encoding visual data in digital format, you might see an analogy between the definition of a digital image, and the definition of a digital audio recording as described above. Naively, it’s tempting to draw a comparison – the greater the frequency, the greater the ‘resolution’; the more accurate the reproduction. Intuitively, this seems reasonable. However, after a point, in reality it becomes categorically fallacious. Here’s why.

Human beings can hear frequencies from approximately 20 Hz to 20000 Hz. This upper range begins to degrade from the age of eight or so. Digital audio can be (and is) filtered, so that sounds at inaudible frequencies are removed from the recording by the time it is transferred to the medium used to deliver music (or spoken word, or bad Rush albums, or whatever). This next point should be obvious but I’ll state it here anyway – removing the representation of inaudible sound from a digital audio recording makes no (zero) difference to the experience of listening to it.

Here’s the critical point. It has been known since the 1940s that a sampling rate of twice the highest frequency to be encoded is sufficient to capture a signal losslessly. There exists a mathematical proof for this, published by an American mathematician and electronic engineer named Claude Shannon. This is why CD audio is represented at more than 44,000 Hz. Digital audio is based on this principle. A higher sampling rate than 44.1 khz simply cannot improve the fidelity, or ‘resolution’ of human-audible material by the slightest degree – in theory, principle or practice.

This is a hard, well-established and indeed proven fact. Anything which contradicts it is marketing nonsense or simple ignorance.

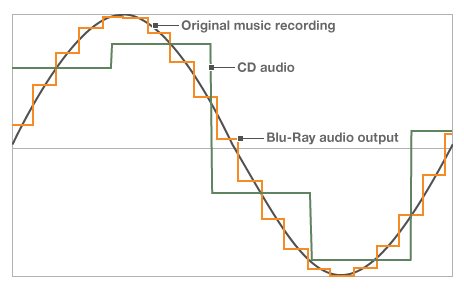

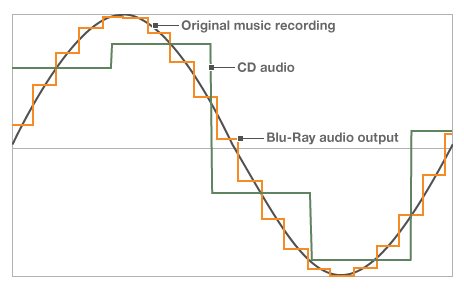

Nonetheless the sampling rate fallacy is widespread; one of the most successful urban myths of modern times. Here’s an image snatched from a BBC website page about digital audio, which attempts in part to show, entirely mistakenly, why a higher sampling rate represents a waveform more accurately.

On the face of it it looks compelling, doesn’t it? Look how much more accurately the Blu-Ray audio samples seem to track the waveform labelled “Original music recording” than the crude, stepped samples of the CD audio data.

But actually, they don’t. The Blu-Ray audio sampling rate cannot in any circumstances provide more information than the CD sampling rate to reconstruct the waveform. This is a corollary of the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem described above.

Now let’s examine the other important measure of a digital recording – the bit depth. This governs the range of values that can be used to represent a single sample. This is not such a cut and dried issue as the sampling rate in theory, because a 24-bit number for example can, undoubtedly, pinpoint an analogue value with greater accuracy (ie less error) than a 16-bit number, as used by CD audio. A 16-bit number allows one of 65536 discrete values to represent the sample, whereas 24-bit allows one of 16777216 values to be used.

The difference between the value to be encoded and the value selected from the range to represent it, the ’rounding error’ in other words, is known as the quantisation error.

In practice though, what happens is this: during the process of converting the analogue signal to audio, a tiny quantity of white noise is added to the signal. This practice is known as dithering, and its purpose is to make the quantisation error independent of the source recording – in other words, the error / distortion is all in the noise. Without dithering, 16-bit audio would give you a slightly distorted version of your source recording. Dithering allows an undistorted, completely accurate representation of the source, plus a little noise.

Here’s the important point – in 16-bit audio, you can’t actually hear the quantisation noise. To discern it at all, you would have to have exceptional hearing. You’d also need to be listening to an extremely quiet passage of your recording in a soundproof room, using remarkable equipment, at a volume that would render you deaf (seriously – literally deaf) when the drums kick in.

To be clear, bit depths greater than 16-bit do have a legitimate purpose in the recording process, because audio data can be re-encoded many times in a studio, with a little error being introduced in each new generation. This means that the quantisation error is multiplied, potentially hundreds of times, in the production of consumer audio – which introduces a risk that it might eventually become audible. 24-bit recording and processing minimises the cumulative error and can prevent this.

However as a medium of delivery to the listener, no purpose whatever is served by encoding the final product at more than 16 bits, at least for human listeners.

What does all this mean? For regular two-channel stereo, the so-called “high definition” audio formats don’t actually work. They cannot offer a higher resolution, or greater fidelity listening experience than that offered by the existing CD audio format. It’s not the case that the difference is too subtle to be discernible on most equipment, as some imagine. There is no audible difference at all.

Why do they even exist, then? That of course is down to the power of big numbers in marketing, and the potential to make people pay more money for a format that, intuitively, seems as though it should be superior.

Naturally, these formats are popular among those members of the audiophile community without the technical nous to know any better. They offer tremendous opportunities for equipment snobbery. Many will even tell you that they can hear a difference, but their credulous faith in “high-definition” audio places them squarely in the same category as the advocates of astrology, religious belief and homeopathy; concerns similarly with no basis whatever in logic, science or reality but sadly no shortage of followers.

It’s important that we resist these pointless formats though, because they are wasteful not only of consumer money, but of bandwidth, storage, and CPU time.

It is possible already to purchase music downloads encoded at a sampling rate of 192khz, and a bit depth of 24. One of these will take six times longer to download and take up six times more space on your hard drive than an equivalent 44.1/16 download. It will typically cost twice as much. And it will offer exactly no improvement whatever; not the slightest difference in “resolution” or “definition” than a standard CD.

If, thanks to the marketers and the gullible audiophooles who are their useful idiots, one of these ridiculous formats should eventually become the standard for the distribution of digital music, then whether we’ve been conned or not, we’ll all end up paying the price.