One of the more questionable decisions of one of my predecessors at the firm in the Midlands where I work as a system manager was to locate their server infrastructure at a data centre in London, over ninety miles away. Within a few weeks of taking that job I had managed to persuade our managing director that we should relocate our stuff to a state-of-the-art and considerably closer data centre in Northampton. I came up with a plan to move everything with minimal downtime. I’d already moved some of our services to the new place, and by July I had negotiated some downtime with our customers to move the main servers.

On the morning of Friday, July 27th, I set off from my home in Leicestershire to collect the servers from London and take them to Northampton. But it turned out to be a traumatic data centre migration, for me anyway.

I have always been drawn to cheap, second-hand cars. I’ve often spent a couple of thousand pounds on a watch, but it seems like a waste of money to spend more than a few hundred on a car. My priorities are possibly a little skewed in that respect.

My present car, an old Rover 200, had been overheating over the previous few weeks. But it had a radiator leak, and I assumed that was the cause. I was confident that if I kept it topped up, it would get me to London, then Northampton and back. I took two large containers of water with me.

I left Leicestershire early, to give myself plenty of time. It was the day of the London Olympics opening ceremony – not the best day to be driving into London. And it was just as well I did, because there had been a serious accident on the M1 motorway which caused a huge delay. I spent an uncomfortable hour or so crawling along in stop-start traffic in the July heat.

But in the end, I approached London with time to spare. I planned to enter the “congestion charge” zone shortly after 6pm, so I could drive into the centre of the city for free – but I arrived in the outskirts of the city earlier than I intended, so I pulled into a quiet residential road, to park for twenty minutes or so. I perused Twitter and read the news on my Android phone.

It was nice to be in London for the opening of the Olympic Games. I had the radio on and was listening to news and conversation about the Games on Radio Five Live. I switched on the ignition again and the rest of the journey to the data centre was pleasantly uneventful. I entered the congestion charge zone at a few minutes past six. The traffic wasn’t as bad as I’d feared it might be.

I parked outside the London data centre, signed in, then made my way to the rack containing our various servers, equipment rails, power switches, disk storage units, routers and remarkable quantities of power and network cabling – all of which had to be removed, and packed into my car. I started to shut the servers down, then to dismantle everything.

I left the London data centre at about 10:45pm. It took longer to remove some of the equipment from the rack than I’d anticipated, and unfortunately it was a long way to carry all the stuff down to the car, over about five trips – but I wasn’t particularly bothered about that. I had plenty of time. The equipment was stuffed into the boot, the back seat and the passenger seat. I switched on the car radio to listen to news and discussion about the opening ceremony that I’d missed.

But as I made my way up through Islington and toward the A1 heading north, the car started to overheat badly .. I had to stop in a side street and top up the radiator under the cold glow of a street light. I was disturbed by that of course. The engine had had hours to cool down and the air temperature was much cooler now. But I assumed I’d just let the radiator leak out too much water.

However to my profound discomfort, the same thing happened again only a few miles up the A1, on the outskirts of North London. I’d only travelled about seven miles. I had sixty-five miles to go. I pulled into a nice suburban street off the A1 in Hampstead to let it cool for 15 minutes, topped it up thoroughly and burped the cooling system. Happily, it started to run normally for a bit. I steered the car up the A1, onto the M1 motorway and out of London.

I managed to get to the first services on the M1, six miles further on, without overheating. I replenished my supply of water from the gents’ toilets, topped the radiator up again, and let the engine cool for another ten minutes. Clearly, it was going to be a long night.

I’d got another twenty miles or so further up the motorway before the temperature needle started to climb again. I took the next junction off the M1 and topped the radiator up again at a building site a few hundred feet from the motorway. Needless to say, I was more than slightly stressed at this point. But I got back on the M1 and made it to the next services – Toddington I think – and repeated the exercise. I did the same again at Newport Pagnell, another twenty minutes up the road. It was a very uneasy ride along the motorway, glancing at the temperature gauge every few seconds. I’ll never forget the sinking feeling of seeing the needle start to climb on that gauge. I was taking it slow – it seemed less prone to overheating under 50 mph. But that just made the journey more agonising. The temptation to put my foot down a bit to get to the next services was surprisingly strong, yet I knew that would only diminish the probability of making it there.

I had managed to get onto the A45, only a tantalising five miles or so away from the comfort of the new data centre and the satisfaction of a mission accomplished, when the engine died.

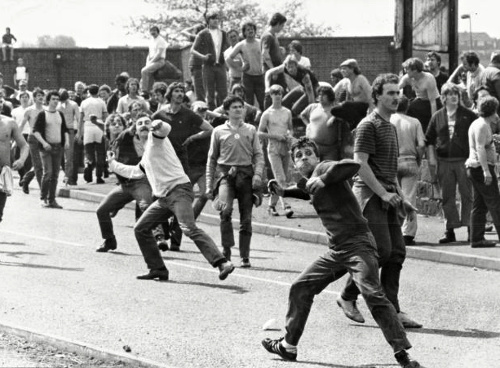

It wouldn’t restart. I was in a horrendous position, just off a big roundabout on a main road into Northampton. From the grass verge, I called the AA – that’s the Automobile Association, the people who send a mechanic and a tow truck to your rescue – while watching the occasional huge lorry swerve round my car. But there was no answer. I gave up getting through to them after about ten minutes – they were extremely busy, even at 2:30 in the morning – and in desperation, attempted to restart the car again.

To my surprise, it did actually start, albeit it was running like a crippled dog through superglue-enhanced treacle. I limped it forward in third gear, watching the “distance to go” figure on the SatNav slowly ticking down .. three miles .. two and a half .. please just get me there!

It juddered to a halt again, with only one mile to go. This time I decided the game was up. I’d have to admit defeat, get the AA to take me home and borrow the other half’s Volkswagen Polo to take the servers back to Northampton the next day. I called them, and got through to an operator this time. He estimated that they’d have someone with me at 04:55. It was now about 3 AM.

I left the car and walked around in the ghostly light of a nearby industrial estate. I was starting to feel cold now, and vulnerable. I could hear shouting in the distance. After perhaps twenty-five minutes of this, I attempted to fire up the engine once again, more in desperation than expectation.

But to my surprise and delight, with a lot of encouragement from my foot on its accelerator pedal, my old motor coughed into life again. I carefully eased it into gear and delicately propelled it forward, glancing nervously at the SatNav every other second. To my relief I managed to nurse it to the security gate at the data centre, where it hissed oil-scented steam from the sides of the bonnet as I announced my arrival into the intercom.

My old Rover literally went that extra mile for the company. It snatched victory from the jaws of defeat with its dying breath. I’d made it. I was elated, or as elated as anyone can be at that time of the morning.

The security guard who was the only person present helped me to lift the bigger servers out of the car. A very helpful and friendly guy, I must say. I helped myself to some coffee and a packet of Swizzlers from the free sweet bucket to get my caffeine and blood sugar levels up a bit, then set to work bolting and cabling the stuff into the new rack. I decided to take it nice and slowly and make it an all-nighter, to give the AA time to work through their backlog of distressed motorists. The Olympic Games and the accident on the M1 had given them a busy night.

I’d bolted everything in, hooked everything up and checked the servers were all working properly and on the air with their new IP addresses, firewall configs, host files and so on by 06:25 or so. The AA man arrived at about 07:20. After a brief inspection, he confirmed my suspicion; the head gasket had blown. It wasn’t an economic repair. Not on that car, anyway.

He hooked the car up to the back of the tow truck while we exchanged small talk about the Olympics. I climbed into the cab, and we set off for home. I got there about an hour later, thanked the AA operative as he unhooked the dead Rover, then went to bed after dutifully listening to a lecture from my wife on the wisdom of buying cheap cars. A couple of days later I called a local company to come and take away the Rover for scrap. I think they gave me £150 for it.

I do hope I won’t have a day as memorable as that one in 2013. Happy New Year!